Text retrieval is the problem of retrieving a ranked list of documents given a query. This post compiles a brief overview of the field of text retrieval research as it stands in 2022.

Retrieval is used in lots of real-world products, including search engines for consumer use, and document retrieval systems used in law and medicine.

There are entire conferences on information retrieval, like TREC, which started in 1992, and SIGIR, which was founded in 1978 (!). However, these days, many of the state-of-the-art models used for retrieval are based on deep neural networks. The lines have blurred and you can find lots of work related to retrieval at NLP conferences like EMNLP and NAACL as well as machine learning conferences.

Text retrieval is a fast-growing field, and this post will try to summarize some of the most important ideas in the area. We’ll inevitably leave some important things out but hopefully the outline here is enough to get someone from knowing nothing about the field to having an idea of what problems people are working on nowadays.

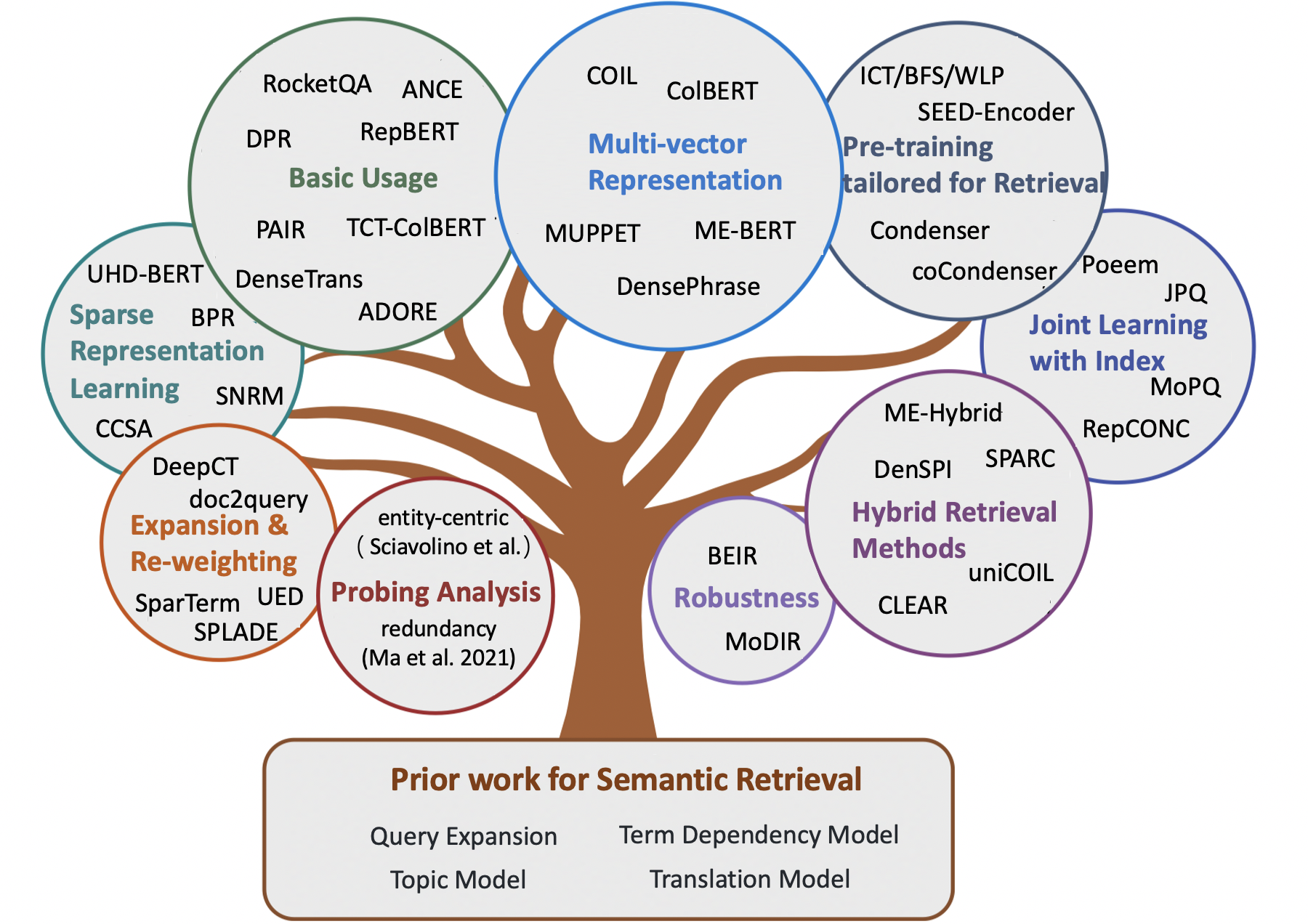

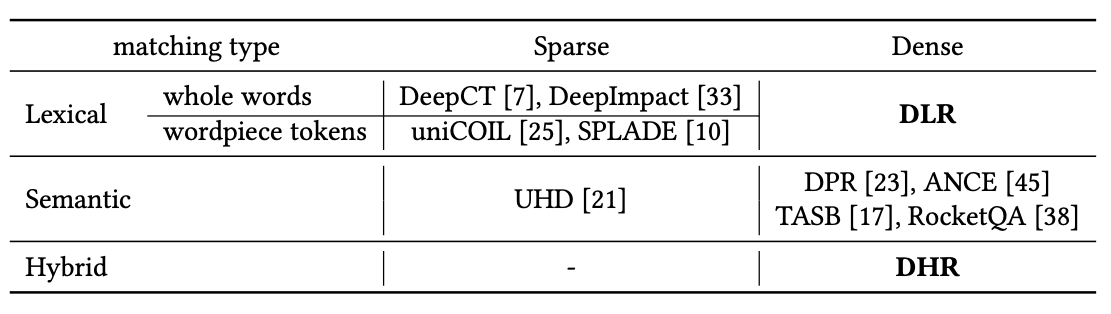

Text retrieval methods are often classified as one of two types: lexical, or word-based methods, and semantic methods that go beyond the word level and try to determine document relevancy by actual meaning. Machine learning techniques have proved most promising for semantic retrieval; decades-old algorithms for lexical retrieval are still considered very good. The figure above taxonomizes a selection of approaches to semantic retrieval.

Retrieval, basically

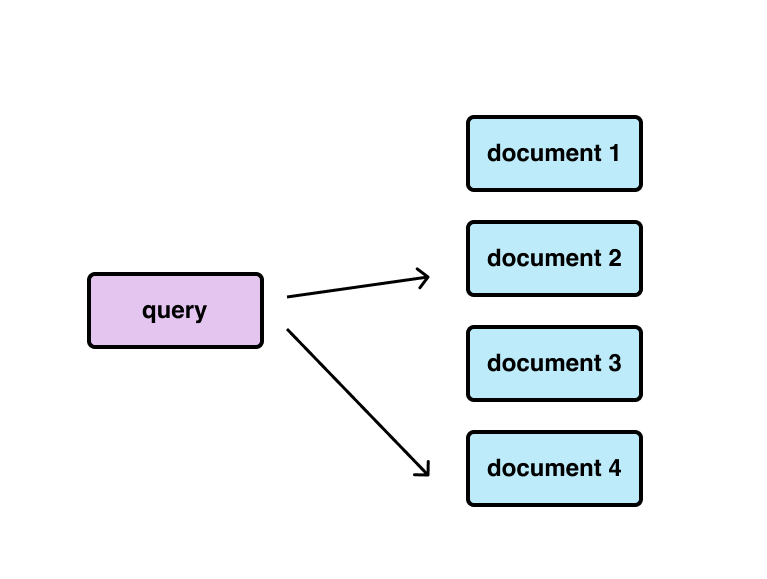

Given a query $q$ and a list of documents ${d_1, d_2, \cdots, d_n}$, the goal of retrieval is to rank the documents based on their relevance to the query. We can formalize this and say the goal of retrieval is to produce a probability distribution over documents, $p(d_i \mid q)$.

Given the query $q$, we can express the relevance of document $d_i$ as the similarity (for some notion of similarity) between $h$-dimensional vector representations $\phi(q)$ and $\phi(d_i)$, where $\text{sim}$ is some similarity function [1]. Then we can write out the probability of $d_i$ given $q$ based on this similarity, normalized over all documents in the collection:

\[p(d_i \mid q) = \dfrac{\exp{\text{sim}(\phi(q), \phi(d_i))}}{\sum_j \exp{\text{sim}(\phi(q), \phi(d_j))}}\]This equation can be used to describe all of the current best approaches for text retrieval, regardless of the type of approach (i.e. whether or not it uses fancy machine learning) or the type of vector encoded by $\phi$ (i.e. dense vectors, sparse vectors, or mixed).

Since this equation describes the full universe of methods for text retrieval, we can see that the game is essentially to produce good representations for $\phi(q)$ and $\phi(d_i)$ with respect to some similarity function $\text{sim}$. Some recent work shows that the choice of $\text{sim}$ doesn’t really matter, and a reasonable choice of similarity function like cosine similarity or dot product should work equally well. The challenge in retrieval, then, is learning a good $\phi$.

Note on search engine “indexing”, and precomputing the document vectors

What if $\phi$ is slow to compute? If the number of documents is large, it may not be feasible to recompute $\phi$ for each document at search time. It makes more sense to precompute all $\phi(d_i)$ and compare the cache representations to $\phi(q)$ for a new query. In this way, we only have to run $\phi$ once, to compute $\phi(q)$ for each new query. This step to precompute and cache document representations is called indexing in search engine lingo.

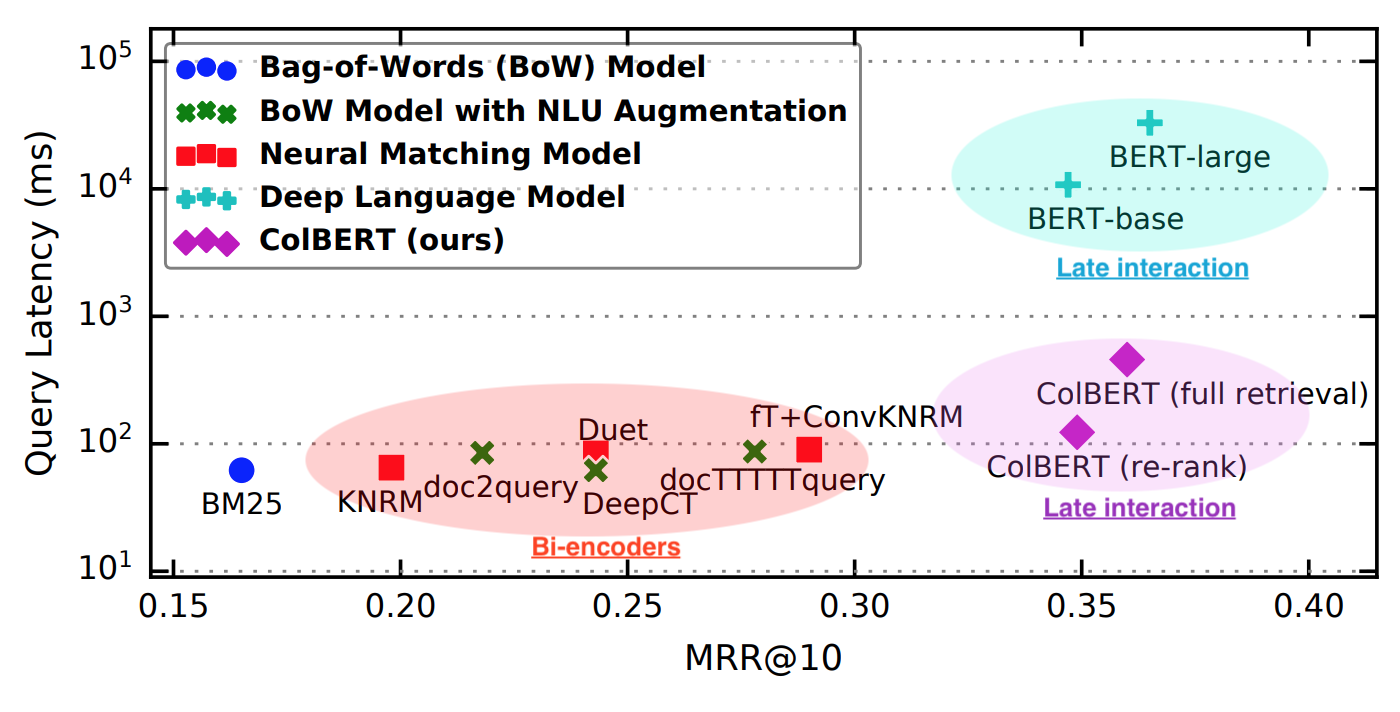

On modern GPUs, computing the similarity between $\phi(q)$ and all $\phi(d_i)$ can be run as a very fast matrix-vector product. However, this enforces a very strict constraint in that each $\phi(d_i)$ has to be completely independent of $\phi(q)$ until the dot product. We’ll see a spectrum of approaches that have been developed, ranging from precomputing everything (the “biencoder” model: fastest, worst performance) to recomputing all document representations on-the-fly (the “cross-encoder” model: slowest, best performance).

Metrics

Metrics given binary relevance

How do we evaluate a retrieval model, given it produces a distribution over documents $p(d_i \mid q)$? The simplest metric might be just accuracy: compare $\arg\max_i p(d_i \mid q)$ to the “true” document over some set of queries and true documents. This metric isn’t robust, however; due to its all-or-nothing nature, accuracy would also make it difficult to compare two very similar retrieval algorithms without a very large evaluation dataset.

A more meaningful metric might be mean rank: after ranking all documents based on $p(d_i \mid q)$, what is the average position of the true document? An ideal retrieval model might have a mean rank of 1, since it would always assign the most probability mass to the true document. However, in practice, a rank-based metric can easily be dominated by a few bad ranks. For example, the mean rank for ranks $[1, 1, 500, 1, 1, 1]$ would be $101$, which would be higher (worse) than an algorithm that gave only ranks of 100, which would have a mean rank of $100$.

The simplest way to deal with this issue is by taking the multiplicative inverse of the rank of each answer and averaging the reciprocal ranks: this metric is called mean reciprocal rank (MRR), and is a commonly-used statistic to compare retrieval systems. The MRR of the examples above would be $0.83$ and $0.06$. Since higher MRR is better, by this metric, the method that found the correct document $5$ out of $6$ times is clearly better.

Metrics given graded relevance

So far we’ve only discussed retrieval in the context of deciding “binary relevance”: a document is either considered relevant or irrelevant. Some datasets for retrieval are more complicated than this and contain documents rated on a scale from irrelevant to relevant. This type of labeling is known as “graded relevance”. Metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and MRR can only be computed if we have a binary relevance score for each document. In this more complex case, we need a metric that can accommodate for documents of multiple levels of relevance.

The most common metrics in the literature for evaluating retrieval systems in the case of graded relevance are based on the idea of discounted cumulative gain (DCG). There are several versions of this metric, and we won’t go into too much detail here. The main idea is that more relevant documents should be higher up in the search results. Metrics based on DCG usually take the relevance score of a document and divide it by its position in the results list, and do some sort of averaging. One popular variant of DCG is Normalized DCG (nDCG), which tries to fix a few perceived problems with vanilla DCG. All of these DCG-based metrics are nice because they allow us to compare retrieval methods across multiple datasets, even if they include both binary-relevance and graded-relevance judgements.

IDF-based Methods

The most trusted baseline in text retrieval is the BM25 search engine ranking function.

It is interesting to observe the staying power of BM25. The algorithm is quite simple and first appeared in its current form in TREC 1994, almost thirty years ago. Relative to our current overparameterized, oversized, overpowered large language models, BM25 is interpretable and incredibly simple. Yet it works shockingly well: you’ll still find BM25 listed in the tables of machine learning papers, in some cases still outperforming deep learning models.

LLM-based Methods

How can we use a pre-trained language model for text retrieval? The answer depends on the level of dependence we desire between $\phi(q)$ and $\phi(d_i)$. Solutions range from fully independent biencoders, where $\phi(d_i)$ is encoded without ever seeing $q$, to fully dependent biencoders, where $q$ and $d_i$ are jointly encoded to produce a score.

Biencoders (Independent)

One approach is to use a pre-trained language model to produce encodings for the query and document completely independently, and compute $p(q \mid d_i)$ directly from their dot product. This approach was pioneered with the model DPR [3], is computationally cheap, and works reasonably well. Many follow-ups have been proposed to scale up DPR and make it work across a broader range of corpuses such as RocketQA [4], GTR [5], and Contriever [6]. These approaches build on the biencoder architecture and try to improve it with different training objectives and more and better data.

Pre-trained models don’t work very well for retrieval out of the box, which is why the mentioned approaches all do some sort of fine-tuning. One recent work argued that pre-trained masked language models like BERT don’t learn the necessary skills through their pretraining task, and proposed the Condenser [7], a pre-trained model designed specifically for text retrieval.

Cross-encoders (Dependent)

Cross-encoders are in some sense the opposite of biencoders: every document-query score is computed by encoding $q$ and $d_i$ together. Note that in this case, $q$ and $d_i$ are fully independent, so we never produce separate encodings $\phi(q)$ and $\phi(d_i)$ with the neural network; instead, you can think of a cross-encoder as a learned similarity function that uses a transformer and operates on raw input vectors $\phi(q) = q$ and $\phi(d_i) = d_i$. Since most language models these days are transformers, this means that cross-encoders enable full self-attention between the query and each document.

The simplest cross-encoder parameterizes $\text{sim}(\phi(q), \phi(d_i))$ using a single pre-trained bidirectional encoder. The first paper to propose this [8] fine-tuned a BERT model on the MS MARCO corpus.

Although they are powerful, cross-encoders create a massive computational challenge: we need to do a forward pass through the model to get a score for each document. As the size of the corpus grows, using a pure cross-encoder in any real-world setting is impractical. This is why research papers never use a pure cross-encoder; they typically use some kind of cross-encoder for re-ranking the top-K documents. For example, the “Passage Re-Ranking with BERT” paper cited above uses BM25 to retrieve the top-1000 candidate documents and uses a cross-encoder to rerank the top ones.

Note: A press release from Google in 2019 announced that they run BERT on all of the search queries typed into Google. It’s unclear how they actually solve this issue, but we can be pretty certain they’re not running a cross-encoder on every one of your queries paired with every single document on the Web.

Poly-encoders (Late interaction)

A third class of architectures, including “late interaction” models such as ColBERT [2] and ColBERTv2 [9] and Poly-encoders [10], can be considered a hybrid between cross-encoders and biencoders. These methods combine learning representations $\phi(q)$ and $\phi(d_i)$ with a learned similarity function.

Practically, these models work by first encoding $q$ and $d_i$ into a multi-vector representation and then computing the score $\text{sim}(\phi(q), \phi(d_i))$ based on a similarity metric $\text{sim}$ that is something more complicated than a dot product. In the case of ColBERT [2] and ColBERTv2 [9], the similarity is based on a “MaxSim” operator. Poly-encoders [10] and other models such as PreTTR [11] and MORES [12] use self-attention-based re-ranking, which is more like a direct composition of biencoders and cross-encoders.

Note that these approaches still require computing similarity between all inputs and documents (albeit much less expensive than full cross-encoding). These works typically demonstrate their effectiveness on reranking the top 1000 documents as returned by BM25, as opposed to ranking all of the documents in the corpus.

Dense vs. sparse retrieval

So far, we’ve seen approaches that operate on a single vector per input (biencoders) and multiple vectors per input (cross-encoders and late-interaction). But all of the approaches discussed so far, except for BM25, have something in common: they operate on dense embeddings. Dense embeddings are feasible for search engines when we parallelize many dot products across GPUs or take advantage of fast nearest-neighbor search via a library like FAISS. But a standard search engine operates on databases called an Inverted Index, which depends essentially on a sparse vector representation. Thus there is still a strong desire within the information retrieval community for effective retrieval methods that use sparse vectors.

The survey paper A Dense Representation Framework for Lexical and Semantic Matching [1] taxonomizes single-vector retrieval approaches based on their matching type (lexical, or bag-of-words approaches, and semantic) and their vector density (dense or sparse). The table above shows some approaches that we haven’t seen so far: notably, there exists one approach to learn semantic sparse vectors [13] and lexically-based sparse vectors [14]. [1] also introduces an approach to “densify” lexical representations.

Objectives for training text retrieval models

Most state-of-the-art systems for dense retrieval (biencoders, cross-encoders, and polyencoders) are trained with some variant of contrastive loss – this is the “learn when things are the same” type in my definition of the three types of contrastive learning. There is a large body of work on making this contrastive loss work better by using more negative samples. This connects to the larger body of work on self-supervised learning, such as vision, to try and improve representation learning with contrastive loss.

The original DPR paper [3] compared the use of random negatives and negatives returned by BM25 for contrastive loss, and also showed that a larger batch size can improve performance. (As discussed in my post about NCE, contrastive loss can be considered an approximation of a larger softmax loss, so it’s no surprise that larger batch size means better approximation means improved performance.) The follow-up work RocketQA [4] showed that using more (including more negatives in a batch) and better (denoised) negative samples helps train better biencoders. Additional work such as ANCE [15], Efficient Training of Retrieval Models Using Negative Cache [16], and LaPraDoR have explored the use of more and more effective negative samples to improve representation learning for text retrieval biencoders.

Learning “unsupervised” retrieval models

There has been a recent push in the text retrieval community to develop models that work well for “zero-shot” retrieval. In this context, zero-shot means that $\phi(q)$ and $\phi(d_i)$ are useful representations on any corpus, even a test corpus without training data. However, the contrastive loss used to train models like DPR and RocketQA relies on labeled documents that correspond to certain queries. How can we apply this contrastive loss in the unsupervised setting?

One approach to learning an unsupervised biencoder proposed in Latent retrieval for weakly supervised open domain question answering [18] is to create positive pairs via an Inverse Cloze Task, predicting which of a pair of sentences was sampled from a provided context.

More recently, the approach proposed in Unsupervised Dense Information Retrieval with Contrastive Learning (Contriever) [6] is to create positive pairs via an Inverse Cloze Task and by cropping two spans from the same document, and treat random examples as negative pairs. They use this method to train a large unsupervised retriever. Most recently, LaPraDoR: Unsupervised Pretrained Dense Retriever for Zero-Shot Text Retrieval [17] uses unsupervised pretraining and a large negative cache to train an unsupervised retriever that achieves state-of-the-art performance on BeIR, the most popular set of benchmark datasets for unsupervised retrieval.

Notable datasets

MS MARCO

The most common training dataset for dense text retrieval models is the MS MARCO reading comprehension dataset [19]. MS MARCO consists of over 1 million question-answer pairs from Bing. Since the training dataset is so large, this was the original dataset used for “pre-training” retrieval models like DPR.

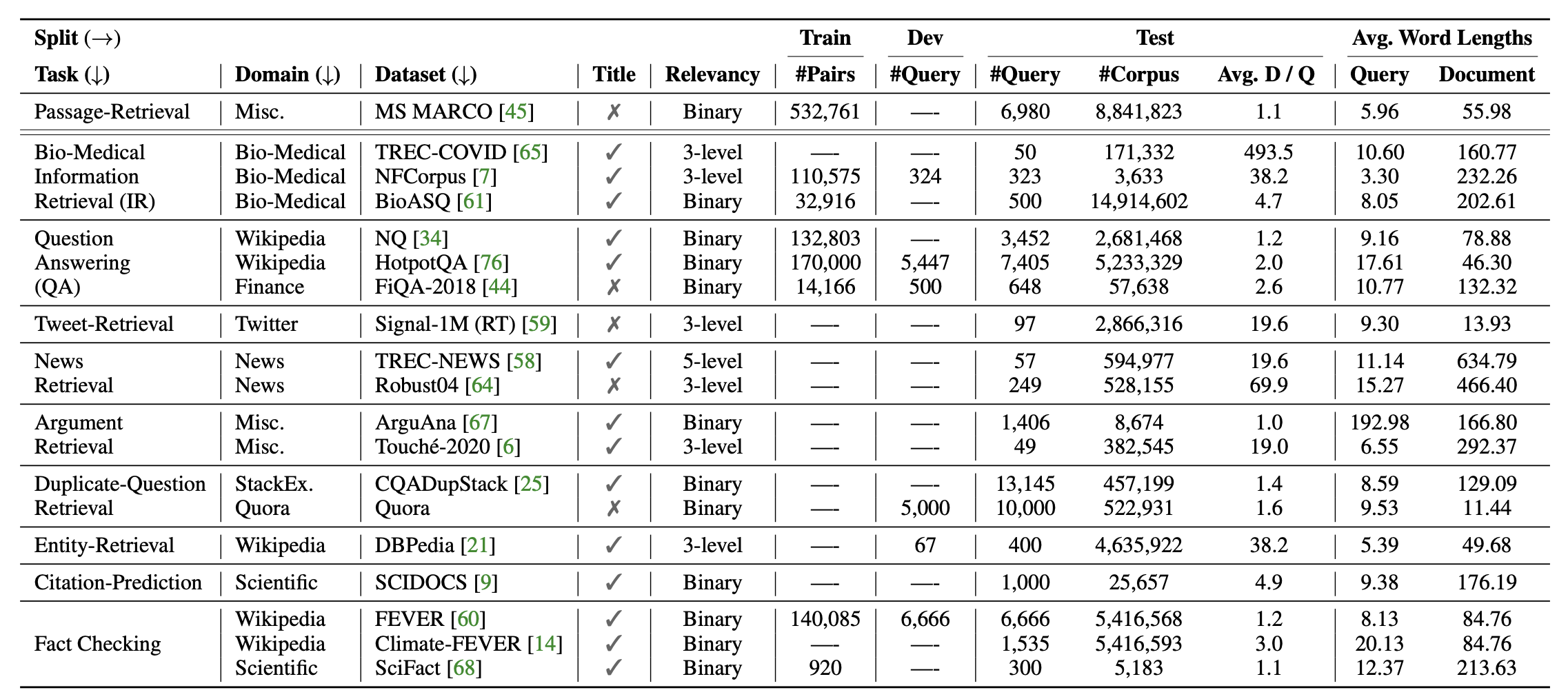

BEIR

A swath of current work on applying large language models to text retrieval focuses on a setup where models are pretrained on some other corpus: potentially unsupervised data like Common Crawl, potentially supervised data like MS MARCO. The main evaluation for new text retrieval models is on the BEIR benchmark [20], a set of eighteen datasets intended for testing retrieval systems.

Notably, the BEIR dataset is about a year old (released in 2021) but BM25 remains a very strong baseline. It outperforms most of the methods benchmarked on the datasets in the original paper (shown in Table 2 of the paper).

Language modeling with retrieval

An interesting related line of work is a line of work developing language models with a built-in retrieval component. These models retrieve documents from a database and generate text conditioned on the retrieved documents. This has a number of benefits: it allows the database to scale independently from the size of the model and enables editing of documents in the database without re-training.

One notable work on training retrieval-augmented transformers is REALM [21]. REALM is a masked language model trained end-to-end to retrieve documents from a large corpus (in the paper, it’s Wikipedia) and use them to answer questions. At test time, REALM is allowed to retrieve a certain number of documents and use them to predict a masked word.

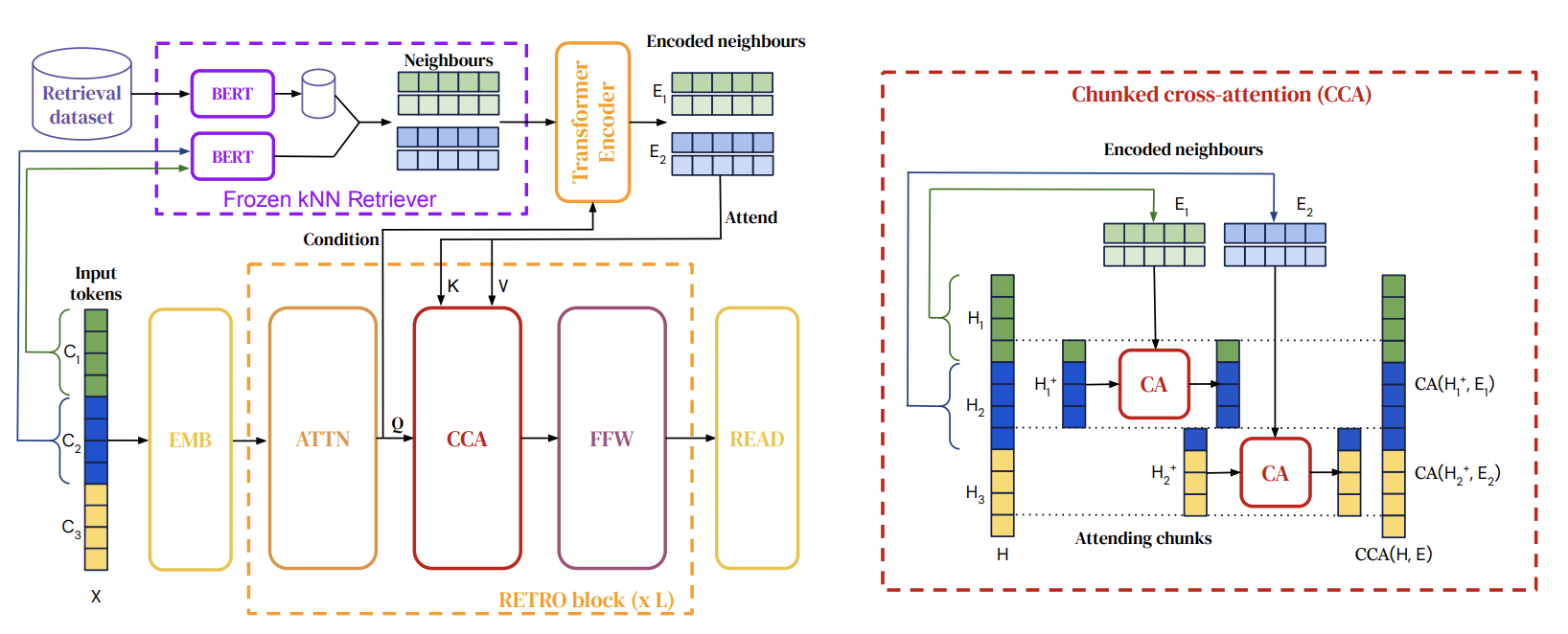

More recently, RETRO [22] (short for Retrieval-Enhanced Transformer) is an example of an autoregressive large language model that works this way; RETRO reportedly works about as well as GPT-3, with 25x fewer parameters. Note that unlike GPT-3, though, RETRO includes a very large (2 trillion token) database, which makes using it challenging in practice.

References

- Lin, S., & Lin, J. (2022). A Dense Representation Framework for Lexical and Semantic Matching. ArXiv, abs/2206.09912.

- Khattab, O., & Zaharia, M.A. (2020). ColBERT: Efficient and Effective Passage Search via Contextualized Late Interaction over BERT. Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval.

- Karpukhin, V., Oğuz, B., Min, S., Lewis, P., Wu, L.Y., Edunov, S., Chen, D., & Yih, W. (2020). Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. ArXiv, abs/2004.04906.

- Qu, Y., Ding, Y., Liu, J., Liu, K., Ren, R., Zhao, X., Dong, D., Wu, H., & Wang, H. (2021). RocketQA: An Optimized Training Approach to Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. NAACL.

- Ni, J., Qu, C., Lu, J., Dai, Z., ‘Abrego, G.H., Ma, J., Zhao, V., Luan, Y., Hall, K.B., Chang, M., & Yang, Y. (2021). Large Dual Encoders Are Generalizable Retrievers. ArXiv, abs/2112.07899.

- Izacard, G., Caron, M., Hosseini, L., Riedel, S., Bojanowski, P., Joulin, A., & Grave, E. (2021). Unsupervised Dense Information Retrieval with Contrastive Learning.

- Gao, L., & Callan, J. (2021). Condenser: a Pre-training Architecture for Dense Retrieval. EMNLP.

- Nogueira, R., & Cho, K. (2019). Passage Re-ranking with BERT. ArXiv, abs/1901.04085.

- Santhanam, K., Khattab, O., Saad-Falcon, J., Potts, C., & Zaharia, M.A. (2022). ColBERTv2: Effective and Efficient Retrieval via Lightweight Late Interaction. NAACL.

- Humeau, S., Shuster, K., Lachaux, M., & Weston, J. (2019). Poly-encoders: Transformer Architectures and Pre-training Strategies for Fast and Accurate Multi-sentence Scoring. arXiv: Computation and Language.

- MacAvaney, S., Nardini, F.M., Perego, R., Tonellotto, N., Goharian, N., & Frieder, O. (2020). Efficient Document Re-Ranking for Transformers by Precomputing Term Representations. Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval.

- Gao, L., Dai, Z., & Callan, J. (2020). Modularized Transfomer-based Ranking Framework. EMNLP.

- Jang, K., Kang, J., Hong, G., Myaeng, S., Park, J., Yoon, T., & Seo, H. (2021). Ultra-High Dimensional Sparse Representations with Binarization for Efficient Text Retrieval. EMNLP.

- Dai, Z., & Callan, J. (2020). Context-Aware Term Weighting For First Stage Passage Retrieval. Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval.

- Xiong, L., Xiong, C., Li, Y., Tang, K., Liu, J., Bennett, P., Ahmed, J., & Overwijk, A. (2021). Approximate Nearest Neighbor Negative Contrastive Learning for Dense Text Retrieval. ArXiv, abs/2007.00808.

- Lindgren, E.M., Reddi, S.J., Guo, R., & Kumar, S. (2021). Efficient Training of Retrieval Models using Negative Cache. NeurIPS.

- Xu, C., Guo, D., Duan, N., & McAuley, J. (2022). LaPraDoR: Unsupervised Pretrained Dense Retriever for Zero-Shot Text Retrieval. FINDINGS.

- Lee, K., Chang, M., & Toutanova, K. (2019). Latent Retrieval for Weakly Supervised Open Domain Question Answering. ArXiv, abs/1906.00300.

- Campos, D.F., Nguyen, T., Rosenberg, M., Song, X., Gao, J., Tiwary, S., Majumder, R., Deng, L., & Mitra, B. (2016). MS MARCO: A Human Generated MAchine Reading COmprehension Dataset. ArXiv, abs/1611.09268.

- Thakur, N., Reimers, N., Ruckl’e, A., Srivastava, A., & Gurevych, I. (2021). BEIR: A Heterogenous Benchmark for Zero-shot Evaluation of Information Retrieval Models. ArXiv, abs/2104.08663.

- Guu, K., Lee, K., Tung, Z., Pasupat, P., & Chang, M. (2020). REALM: Retrieval-Augmented Language Model Pre-Training. ArXiv, abs/2002.08909.

- Borgeaud, S., Mensch, A., Hoffmann, J., Cai, T., Rutherford, E., Millican, K., Driessche, G.V., Lespiau, J., Damoc, B., Clark, A., Casas, D.D., Guy, A., Menick, J., Ring, R., Hennigan, T.W., Huang, S., Maggiore, L., Jones, C., Cassirer, A., Brock, A., Paganini, M., Irving, G., Vinyals, O., Osindero, S., Simonyan, K., Rae, J.W., Elsen, E., & Sifre, L. (2022). Improving language models by retrieving from trillions of tokens. ICML.